A flash card language app to help break the language barrier

June 2021

Applying design thinking to helping a poorly understood and traumatised community, I worked with Ezidi (also known as Ya'zidi) refugees to help them communicate with the local community.

I delivered this project over five weeks as part of a design course at Academy Xi, a Sydney-based design school, completing an end-to-end design process in a unique problem space.

Project methodology

The problem

My initial understanding of the problem was that refugees in my home town of Armidale were struggling to communicate with the local community, despite having been resettled there for some years. I wanted to understand what was going on, so I framed my initial problem statement based on my initial grasp of the situation.

About the Ezidi people

The Ezidis are a persecuted minority from Iraq. Several hundred were resettled in my home town of Armidale, NSW, starting in 2018, by the Australian Government. I was motivated to help the community interact more easily with the locals, and improve access to work and training opportunities.

Research phase: an exercise in overwhelm

After starting the project, I quickly felt overwhelmed. Desktop research revealed stories of unimaginable suffering and trauma. Not only that, their culture is traditionally closed to outsiders.

Desktop research: harrowing stories and migration data

I also didn't know any Ezidis; most of them didn't speak English. Further, services who looked after them were reticent to give outsiders access. I reached out to local support groups, government agencies, case management/social workers and the local Rotary organisation.

Eventually I gained interviews with the Director of a local case management service. This lead to connections with the Ezidi community and local businesses and farmers who employ them. Formal and observational interviews with these stakeholders formed the core of my research, alongside the extensive desktop research including media articles, academic reports and government migration statistics.

Observing a farming project; usability testing

Synthesis and insights: the pivot

Speaking with the community was humbling and inspiring at the same time: despite the impact of their traumatic past, they look to the future with hope.

The research revealed a nuanced problem space about mental health and trauma, rather different from my original assumption of communication problems due to poor English.

In fact, trauma affects all aspects of Ezidi life, in particular their ability to learn new information such as retaining English vocabulary or writing down their phone numbers and names (most are illiterate, even in their native language, Kurmanji). This dominoes into other areas critical to quality of life: gaining employment, opening bank accounts, accessing welfare payments and renting and buying property.

Arriving in Armidale in some cases added layers of trauma to their situation as a result of learning how to navigate an entirely alien society and government system. Mistrust, fear, uncertainty and struggle remain. Resettlement was no fairytale.

Introducing Aya

While these research insights were overwhelming and unexpected, they helped create a really clear picture of who I was designing for.

I wanted my persona to reflect the humbling interplay of fear, hope and resilience I'd witnessed in my interviewees.

Aya's journey

Aya's journey is a combination of interview insights, demonstrating the pain points Ezidis experience in daily life as a result of being unable to communicate with local services and businesses.

Ideation

Now that I had a clear vision of Aya's journey and pain points, I conducted an in-person ideation workshop in which I brainstormed solutions.

For this session, I based my top “how might we” on the pain points in my journey map to reframe the problem statement more broadly:

"How might we better support the Ezidis' communication with the Armidale community?"

Wrestling with this problem we conducted 'crazy eights,' discussed top ideas and voted.

The idea: flash cards for day-to-day communication

The idea I came up with was a combination of the top-voted ideas from the ideation session and aligned to my research insights. One interview in particular delivered inspiration for my idea.

A local business owner who employed Ezidis had told me how his staff used ‘flash cards’ - a simple photo with the English word underneath. This was the most effective way for them to learn on the job.

Based on that anecdote I chose the idea of a crowd-sourced flash card app concept that would enable both Ezidis and Armidale locals to upload and edit flash cards and translations, creating a living database they could use and update on their own.

I validated the idea against my persona: Aya needed a smartphone app that was simple, with minimal copy and that was mostly image-based, to help her interact with services. As trauma blocks memory, this app could serve to remind and help her learn.

With my research-validated idea chosen, I continued traversing the develop phase of the double diamond.

Storyboarding influenced the creation of user flows, which focused on the one thing I wanted the app to do, its core purpose: make and edit flash cards, rather than making a 'do everything' solution.

Wireframing

The initial wireframes visualised the user flows, focusing on key actions: adding a new card, editing an existing card, and search functionality.

Styling the UI

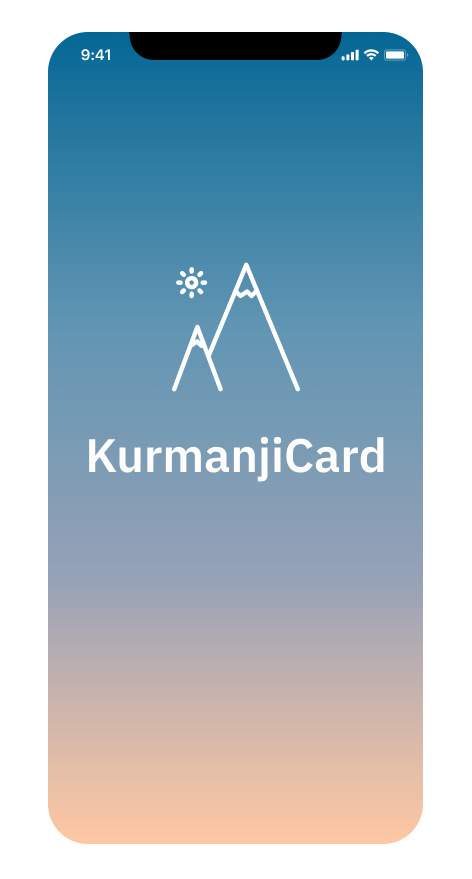

Aya needed a simple interface with minimal copy, focusing on visual cues or images to entice her through the flow.

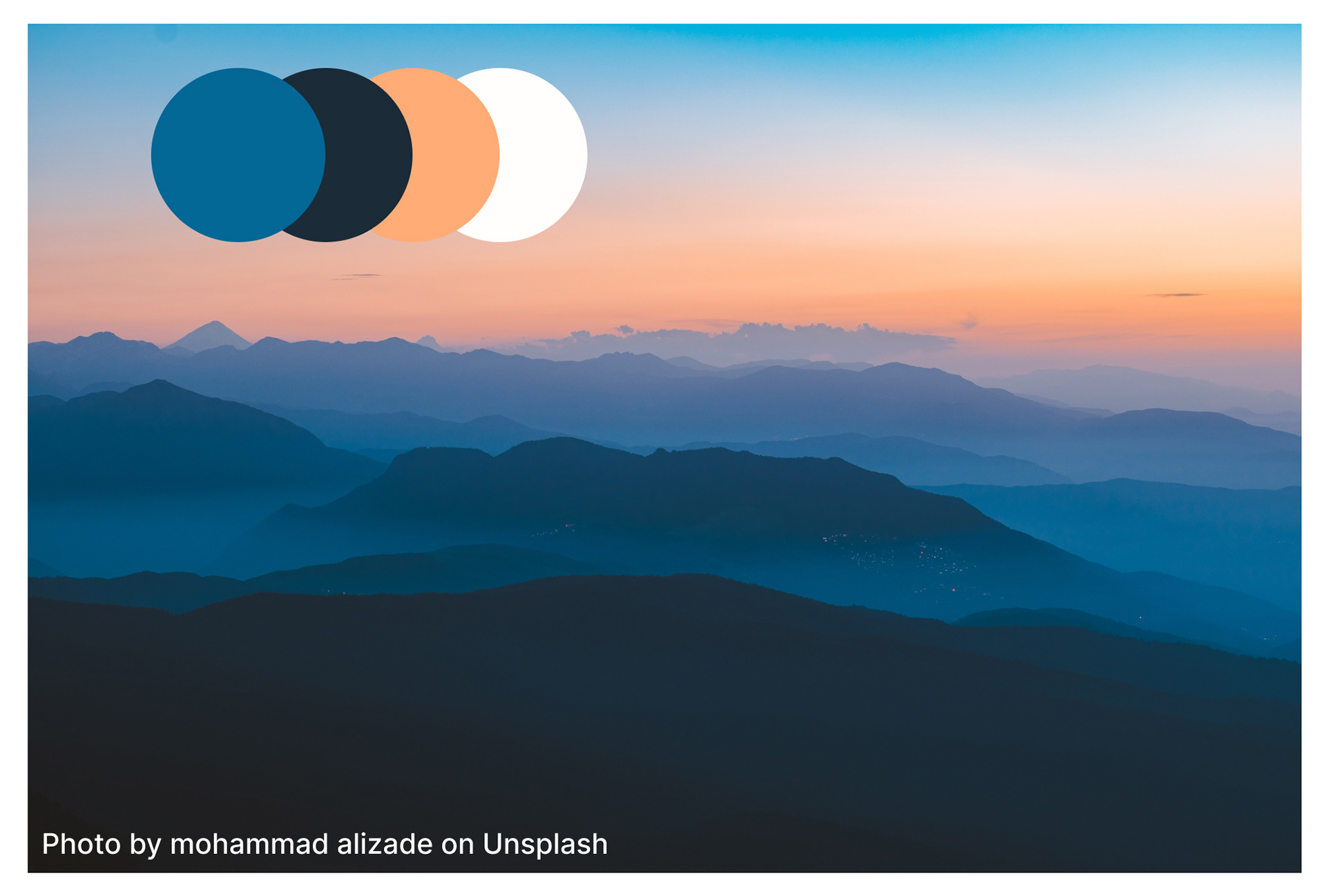

My inspiration for the colour palette referenced the mountain dusk scene below, an inspiring image evoking colours intended to be calming through a mix of warm and cool natural hues.

Mountains are significant for the Ezidis: they are from the Sinjar Mountains in Iraq, which they consider to be sacred. The Sinjar Mountains also served as a literal refuge from the persecution of ISIS in 2014. In an almost poetic journey, they have resettled in Armidale's Northern Tablelands in NSW, a new mountain refuge far from their traumatic experiences.

I wanted to reference this motif of mountains as a reminder of the sacred and the familiar, and to convey a sense of challenge, achievement and resilience, apposite for the Ezidi experience.

Iterate, test, iterate, test...

With limited time to find testing participants, I initially tested my concept with classmates via Maze, which highlighted key issues but essentially validated the idea.

With limited time I moved into live usability testing with Ezidis and locals. I experienced a major setback when testing iteration two with an Ezidi chef who completely misunderstood the concept, and could not read any of the limited copy.

This was a humbling moment where I had to redesign the app to simplify the design further, removing copy where possible and increasing the size of clickable areas.

Luckily I was able to test the design with a member of the Ezidi community who had better English and grasp of the concept. While she identified some areas for improvement, overall her feedback resoundingly validated the concept, saying,

"This could really help my community."

This feedback on its own was incredibly rewarding - I realised the potential of design to create meaningful change.

The final version (so far)

Next steps

The impact of this concept could be immense - with more time to build trust amongst the community, I'm excited to keep testing and iterating the concept, and eventually, building the app with a developer partner. Watch this space!